Robert Lighthizer’s recent New York Times op-ed presents a dire view of US trade policy, arguing that trade deficits, foreign ownership of US assets, and policy failures have left the country vulnerable. His solution? An elaborate new system of tariffs designed to enforce balance in bilateral trade. But this one-dimensional argument is built on a misleading interpretation of data and an outdated understanding of trade; it’s also simply unrealistic.

There is a balance of payments where US deficits in goods and services trade are offset by net capital inflows. Without digging too deep into the data, one can do a little accounting on both sides of the ledger sheet to see that the US trade and investment positions are not the lose-lose situation that Lighthizer claims. Foreign capital plays an important role in financing US growth; US services exports are a key strength ignored when focusing on goods trade; and bilateral trade imbalances—when examined closely—do not support his theory that foreign trade partners running a surplus are engaging in wholesale predatory behavior at the expense of their own citizens.

The Misleading $20 Trillion Foreign Wealth Transfer

One of Lighthizer’s central arguments is that the US has “transferred” $20 trillion of its wealth to foreign entities. The implication is that the country has been drained of resources due to trade deficits, leaving it at the mercy of foreign creditors. But this is a misrepresentation of what these international investment flows mean in practice.

The $20 trillion figure he cites refers to the net international investment position (NIIP), which measures the difference between US-owned assets abroad and foreign-owned assets in the United States. When we look at gross versus net figures, they tell a different story: As of Q3 2024, US assets abroad totaled $37.86 trillion, while foreign-owned assets in the US stood at $61.46 trillion, resulting in a net investment position of -$23.60 trillion. This is not a one-way loss. It is a reflection of the US economy’s attractiveness to global investors. The “wealth” wasn’t transferred to foreigners; they bought it. Owning US stocks, bonds, and real estate has been a pretty good investment in recent years, and the US has long been the top global destination for foreign direct investment. If we flip this around and see US investors buying foreign stocks for their retirement portfolios, we wouldn’t say foreign wealth was transferred to US retirees.

If foreign ownership of American assets is framed as a failure, then logically should we conclude US ownership of $37.86 trillion in foreign assets is somehow exploiting the rest of the world? It’s just not a serious argument. American companies have invested heavily abroad—whether it’s Ford in Mexico, Apple in China, or Coca-Cola in Europe—and those investments are seen as a sign of US multinational firms’ economic strength. (They also, as my colleague Scott Lincicome recently noted, invest heavily here too, reflecting the often-complementary nature of US multinationals’ domestic and overseas investments.)

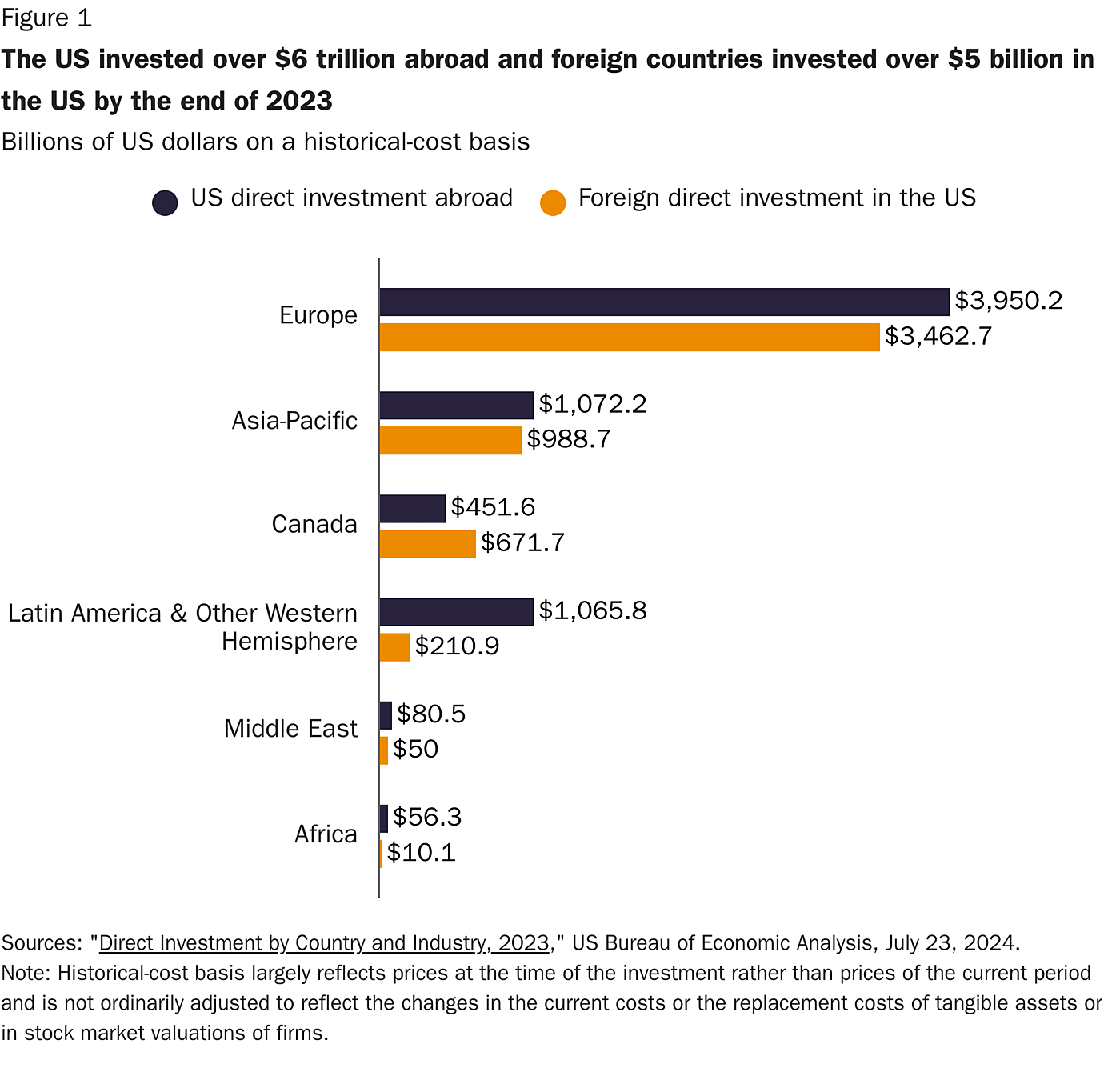

One need only look at the latest figures from the BEA (reproduced below) on outward and inward foreign direct investment to see this is a two-way street. The United States has over $6 trillion in outward FDI in Europe, the Asia-Pacific, and Latin America combined. Likewise, foreigners have invested in the US. For example, Japan’s Honda builds the Accord in Ohio, Korea’s Kia has manufacturing facilities in Georgia, and Germany’s BMW has operations in South Carolina and elsewhere.

Those Who Dismiss Comparative Advantage Are Doomed to Forget the US Is a Leading Service Sector Exporter

Lighthizer’s analysis focuses almost exclusively on bilateral goods trade deficits, reinforcing a narrative that the US is losing to countries that export more goods to America than they import. But this overlooks a major component of US trade: services. That’s a problem when your only solution to trade deficits is a tariff on goods.

The United States is a global leader in services trade, running large trade surpluses in key sectors such as finance, education, tourism, technology, and R&D. The same countries where the US runs a goods trade deficit—such as China, Korea, and Japan—import billions of dollars in US services such that the US runs an overall trade surplus in services with the world. In many cases, these surpluses offset the goods deficit, making the overall trade relationship far more balanced than Lighthizer suggests.

The United States runs both a goods and services surplus with some countries too. In 2023, the US surplus with Australia was $32 billion, of which 45 percent was services. The US had a $60 billion surplus with the Netherlands, of which 32 percent was in services. I think the Australians and the Dutch would be surprised to learn, using Lighthizer’s logic, that they were being exploited and made poorer due to the US trade surplus.

When I dug into the disaggregated data from the BEA, what I found reaffirmed a simple lesson of international economics. The pattern of trade is related to comparative advantage. Countries tend to specialize in the exports of goods or services where they are relatively more productive and import the goods or services where they are relatively less productive. Sure, the US runs a goods trade deficit with 45 of the 79 countries and groups where the BEA tracks goods and services separately.[1] But it runs a services trade surplus with 54 of them.

Most economists, including me, will tell you bilateral trade balances are not how we score trade and economic policy. But if you’re going to do it, you better not leave your best players back on the practice field when you propose a new global taxation system for trade. If the US were to demand strict “balance” in trade through an agreement with automatic tariff triggers on surplus countries, it could come at the expense of its comparative advantage in services.

To meet Lighthizer’s vision, the US might have to request countries to cut back on American services imports, increase their goods exports to the US, or accept that they might even have to put tariffs on US services exports to “solve” the imbalance. Try getting Congress to pass that bill.

Which brings us back to why the obsession with bilateral imbalances doesn’t make much sense. Americans don’t want to buy more imported agricultural goods and pharmaceuticals from Australia to close the US-Australia trade gap, and neither country is worse off for ignoring it. In effect, Lighthizer’s plan would mean disrupting some of America’s most competitive industries just to satisfy an arbitrary and incomplete scoring system.

Do Trade Surpluses Signal Export Promotion Is Suppressing Foreign Consumption? No.

A key premise of Lighthizer’s argument is that countries running trade surpluses with the US are deliberately suppressing domestic consumption to boost exports. But the data do not support this conjecture.

If Lighthizer were correct, then to first order, we would expect a negative relationship between a country’s trade surplus with the United States and its per capita gross domestic product—in other words, by Lighthizer’s math countries running large surpluses with the US should be poorer. But there is no such relationship. Germany’s economy, for example, has been stuttering along in recent years, but it just hit a record trade surplus with the US.

To confirm this, I computed the bilateral goods trade balance in 2023 and compared it to the latest GDP per capita data for 190 countries. I defined a goods trade surplus as US imports minus exports to each country (e.g. a positive surplus means the US has a trade deficit in goods, but the opposite means the US runs a surplus of its own).

Overall, and as the figure above shows, there’s simply not a strong relationship between a country’s goods trade balance with the United States and its income. The linear fit to this relationship has an R‑squared of 0.5 percent. Some rich countries have surpluses; some low-income countries do too; and we need to look elsewhere to assess how their policies affect their economies and ours.

Like so many protectionists today, Lighthizer’s argument is heavily China-centric, drawing broad conclusions from a single country’s model of state-driven economic development. But most trade surplus countries do not follow the same playbook as China. South Korea and Germany, for example, have high domestic consumption and strong worker protections. Lighthizer’s sweeping claims fail to capture the diversity of economic models that exist in surplus nations, and they collapse when other countries are considered.

We Can’t Base a New International Trading System on a Flawed Premise

Lighthizer’s policy prescription—a system where tariffs are automatically imposed whenever a bilateral trade deficit reaches a certain threshold—is deeply flawed. It assumes that trade imbalances are purely the result of policy choices, ignoring the role of investment, financial flows, supply chains, and consumer preferences.

Moreover, trade imbalances are inherently linked to capital flows. A country that runs a trade deficit—such as the US—must also run a financial account surplus, meaning it attracts investment from abroad. Lighthizer’s tariff mechanism would disrupt this balance, potentially reducing foreign investment in US businesses, real estate, and financial assets. It also, as economic theory and practice both show, would perversely reduce US exports.

Lighthizer invokes John Maynard Keynes to justify his idea, but conveniently omits an important detail: Keynes’s vision was not for new tariffs but a strong, centralized international regulatory framework that no U.S. administration would ever accept. The US rejected Keynes’s original Bretton Woods proposal for an international clearing union after World War II, precisely because it would have impinged on national sovereignty. If only this were his worst mistake.

Lighthizer’s argument relies on an outdated and one-dimensional view of trade. His laser focus on bilateral goods deficits is misleading, his claims about foreign wealth transfer distort the actual data, and his assumption that trade surpluses signal economic weakness and exploitation is unsupported by evidence.

Rewinding the clock to an era when diplomats worked out deals in New Hampshire hotels will not help 21st-century American workers and businesses thrive in the global economy. The United States should welcome foreigners to Bretton Woods once again, but not to negotiate an antiquated trade agreement. We should encourage them to go skiing, play golf, and help increase U.S. service sector exports.

[1] The Bureau of Economic Analysis only disaggregates goods and services trade into 71 countries and then groups some smaller trade partners into 9 separate regional aggregates (e.g. “South and Central America, other”).